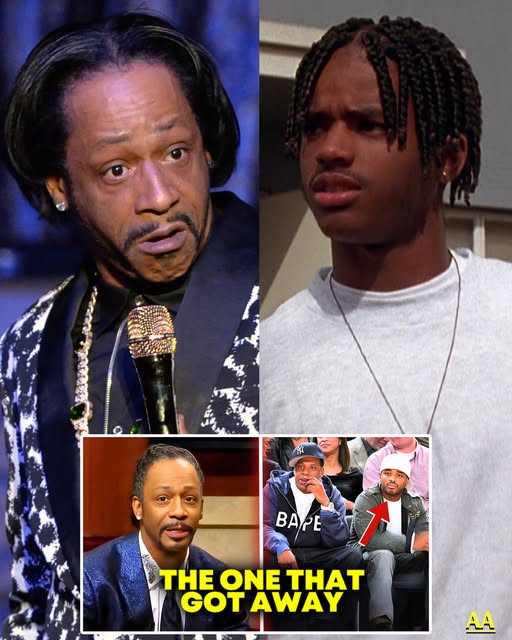

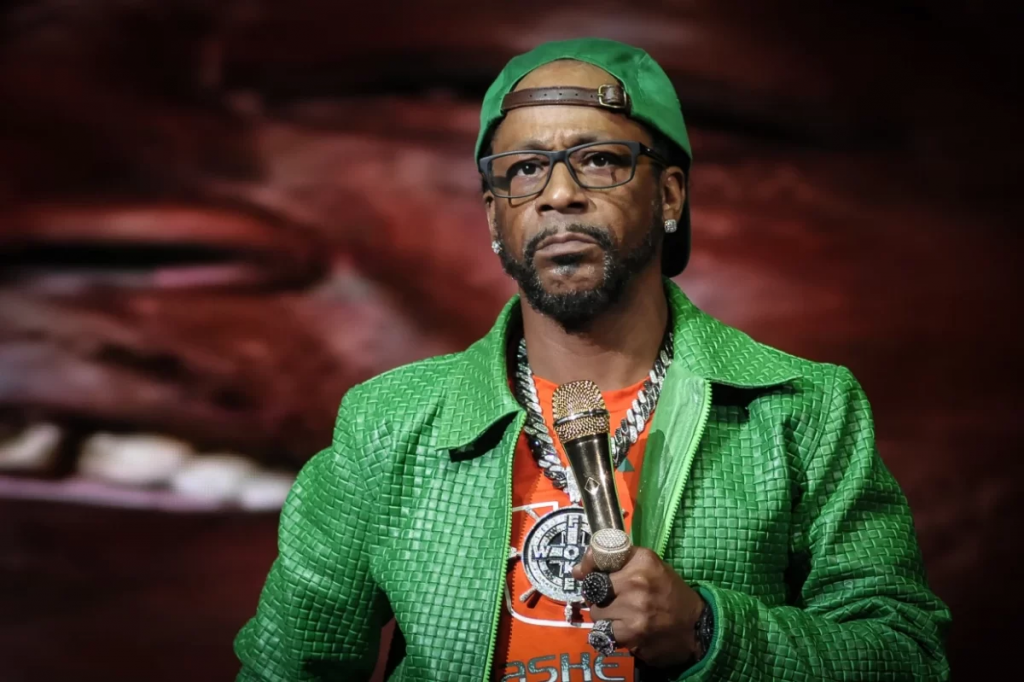

For years, comedian Katt Williams has called out Hollywood for the way it treats Black artists. In his eyes, the industry doesn’t want authentic, principled people—it wants puppets who will follow the rules, play along with behind-the-scenes “rituals,” and never challenge the system.

Williams’ warnings have become especially relevant when looking at the career of Larenz Tate, a star who seemed destined for greatness but quietly faded from the spotlight.

Larenz Tate made his mark in the 1990s with unforgettable performances in films like “Menace II Society,” “Dead Presidents,” and “Love Jones.”

He was the leading man Black America could root for: talented, charismatic, respected by men, adored by women, and never caught up in scandals. But as quickly as he rose, Tate vanished from major Hollywood roles—without controversy, arrests, or public meltdowns. The industry simply stopped calling.

So, what happened? Katt Williams never named Tate directly, but he’s long hinted that Hollywood’s gatekeepers push Black actors into compromising situations.

According to Williams, those who refuse to “bend the knee”—who say no to humiliating or stereotypical roles, like cross-dressing for laughs—are quietly blacklisted. Williams argues that Hollywood only allows a select few respectable Black men to succeed at a time, while the rest are sidelined unless they accept roles that reinforce negative stereotypes or submit to industry rituals.

Tate, by all accounts, refused to play that game. Rumors suggest he turned down roles he felt were disrespectful or demeaning, including those requiring him to wear a dress.

Williams often points out that wearing a dress in Hollywood isn’t just about comedy—it’s a test of submission and control. Once an actor crosses that line, Williams claims, the industry has leverage over them. But if they refuse, their opportunities dry up.

Larenz Tate himself has hinted in interviews that he didn’t fall off—he walked away. He’s spoken out about the persistent pay gap between Black and white actors, noting that Black talent is often undervalued and underpaid, even when they deliver box office hits.

He’s also criticized the lack of Black ownership and creative control in Hollywood, pointing out that true change won’t come until Black creators have the power to greenlight projects and tell their own stories.

Williams and Tate’s experiences echo those of other Black artists like Taraji P. Henson and Mo’Nique, who were labeled “difficult” or “ungrateful” for demanding fair treatment.

Hollywood, Williams says, is comfortable with Black pain and dysfunction—it sells, it’s safe, and it doesn’t challenge the status quo. But self-respecting artists who refuse to sell out or play along threaten the system, so they’re pushed aside.

Despite his absence from the mainstream, Tate’s talent and integrity have made him a role model for many. He didn’t lose his career because he wasn’t good enough—he lost it because he wouldn’t let himself be controlled.

As Katt Williams continues to speak out, more people are realizing that Tate didn’t just fall off—he escaped a system that wasn’t built for real ones.